In April, Kim Woodwell took our friends from Virginia Conservation Network out to visit two solar projects in Mount Jackson. One project is going really well: it’s part of a larger working farm, there are good water quality measures in place and it didn’t involve major grading and compaction. By contrast, the second solar installation they visited is sited on formerly productive farmland, had water and sediment run-off problems during construction, and lacks buffering, wildlife passage and native pollinator plants.

Rural counties have had to develop new expertise in local permitting to make sure critical resources are protected during large-scale construction of solar projects, like this 3500 acre project in Spotsylvania County. (Image courtesy of Piedmont Environmental Council)

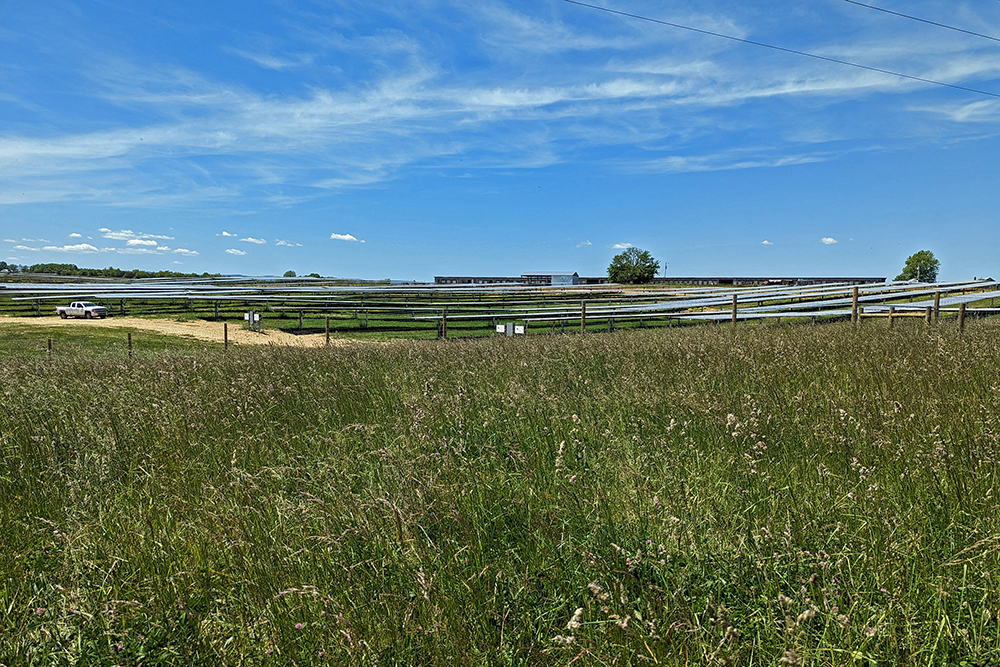

In Shenandoah County, minimal grading and traditional wire farm fencing rather than chain link fencing helps blend this project in with adjacent farm operations. (Image courtesy of Mr. Fred Garber)

This contrast tells an important story. Like any large land use, there are thoughtful projects with multiple benefits and there are projects that aren’t a good fit or cause harm. All green energy projects are not created equal.

In Virginia, many of the siting and oversight decisions for solar projects occur at the local level, and at the Alliance, we have been working for years to push for local policy and incentives that lead to complementary projects and discourage poorly sited or poorly developed projects. Within the last two years, we have provided guidance, examples from other localities and technical resources to Page, Rockingham, Shenandoah and Augusta counties for newly adopted or updated comprehensive plan and zoning ordinances related to solar development.

At the state level, an important step in the right direction was Virginia House Bill 206, legislation passed in 2021 that encourages solar developers to avoid our best farm and forest land when siting future solar projects.

With the right local and state guidelines in place, we hope to see solar projects in the Shenandoah Valley that minimize negative impact and even benefit local communities. This means that instead of building on our best farm and forest land, solar projects go on rooftops, parking lots, and brownfields, like a recent proposal in Rockingham County for a solar installation on a closed gravel and sand pit. Instead of converting an entire family farm to a solar installation, smaller scale projects, say 10-50 acres, can be built on marginal sections of farms, and the lease revenue can help diversify income for the rest of the operation.

If projects are required to be sited and constructed in a way that fits with our agricultural and natural landscapes, solar developers will seek to build these projects.