Good communities don’t just happen. Sometimes, here in the Shenandoah Valley, we take for granted our high quality of life—beautiful landscapes, working family farms, friendly towns and villages, a mix of business and industry that provides good, steady jobs, and abundant clean water and fresh air.

That’s not to say, however, that we don’t have our challenges—especially as we grow. Remember that bumper sticker that made the rounds a few years ago? “Don’t ‘Fairfax’ the Valley,” it read. Not that we have anything against Northern Virginia, but many folks of a certain age remember when that part of the state looked like our part of the state. A visit now is a journey into congestion and urban sprawl where green space and small town friendliness are valuable and hard-to-find commodities.

But as much as we hate to admit it, that part of the state is often where the jobs are and where the housing is, and that leads us to a conundrum—how to maintain our high quality of life and grow in a way that provides housing and jobs while maintaining our “specialness” for the next generation.

Harrisonburg aerial by William Hoyle Garber taken 70 years ago. Source: Shenandoah County Library/Mount Jackson Museum

Meet the comp plan (technically called the comprehensive plan)—the superhero of the planning world. And, just as superheroes have to have their sidekicks—remember Batman had Robin?—the comp plan alone can’t get the job done. Communities need several tools in their planning “toolbox” to carry out the plan’s vision.

First, what is a comp plan? To get the specific answer, one has to look in the Virginia State Code, specifically 15.2-2223 that mandates that every locality in the Commonwealth has to “prepare and recommend a comp plan for the physical development of the territory within its jurisdiction and every governing body shall adopt a comp plan for the territory under its jurisdiction.” That plan, which has multiple components including a map showing where the county would like certain types of growth to occur, provides a locality’s vision for promoting “the health, safety, morals, order, convenience, prosperity and general welfare of the inhabitants.” The plan looks long range—20 years into the future—in a broad, comprehensive way at all aspects of a locality from housing to transportation to open space and economics.

“A comp plan is a guide to show a community how to get to the Holy Grail,” explained Mike Chandler, the Director of Education for the Land Use Education Program at Virginia Tech. Chandler is the guru of comp plans in Virginia. He knows what they can do, what they can’t do, and how to make them work.

“It is a vehicle to chronicle where we’ve been, where we are, and where we want to arrive at in a preferred future. It is a guide to growth and development within a community,” he added.

“A comp plan is a guide to show a community how to get to the Holy Grail,” explained Mike Chandler, the Director of Education for the Land Use Education Program at Virginia Tech. Chandler is the guru of comp plans in Virginia. He knows what they can do, what they can’t do, and how to make them work.

“It is a vehicle to chronicle where we’ve been, where we are, and where we want to arrive at in a preferred future. It is a guide to growth and development within a community,” he added.

He is quick to explain that the comp plan is a vision to guide deliberation and decision-making, but it does not control what happens on a particular parcel of land. That comes with zoning and ordinances that put into law how development will occur and defines what can and cannot happen on a parcel of land within a particular zoning designation. “Together the comp plan and good zoning ordinances provide a powerful one-two punch,” Chandler emphasized.

But even with the loftiest vision of a comp plan and the strictest ordinances, things sometimes go awry. Such is the case in James City County in Tidewater Virginia. Traffic and congestion there have frustrated residents and county planners alike in an area that has seen a rapid surge of commercial and residential development.

“We’re sort of doomed in that stretch for it to get worse and worse because of how many approved developments and people are coming,” bemoaned a recently retired planning commissioner.

The growth he was referring to was not random. Rather it was planned for and directed by the vision of the county’s comp plan and supported with the structure of the county’s zoning and ordinances. So, what went wrong?

“If every acre of land within a designated growth area lived up to its future potential then how many people, how many buildings, how many cars, and how many businesses would that be?”

Here’s where the superhero needs some good sidekicks to win the day. Chandler explained that a good comp plan, even with the teeth of the ordinances, will not necessarily win without some other tools. Tool number one is a good build-out analysis that asks the question: “if every acre of land within a designated growth area lived up to its future potential then how many people, how many buildings, how many cars, and how many businesses would that be?”

“You have to do the mathematics under the existing zoning and then come up with a strategy for how the infrastructure is going to be enhanced or improved to handle that scenario,” he said.

Once planners understand the potential future, then they have to institute phased development, meaning that any new development will not be allowed until the infrastructure—including roads, water, sewer, schools—is there to support the growth.

In addition, localities need to have a strong capital improvements plan in place so that everyone is aware of what infrastructure is needed before a rezoning can take place. “Local governments have to be careful to not prematurely change the zoning before the infrastructure is in place,” Chandler noted.

“Developments have a regional impact,” Chandler noted. Counties and cities should start to fit their comp plan maps together with neighboring localities and begin to think regionally about shared boundaries and working together to accommodate growth, shared infrastructure, and common issues.”

He pointed to several localities across the state that provide good examples of how to time infrastructure improvements with the execution of rezoning to make sure that their comp plans live up to their potential. Probably two of the longest-standing examples of using all of these tools to fulfill the comp plan’s vision, he said, are Fauquier and Albemarle counties (1956 and 1980). “Albemarle decided that 95% of the county was going to remain agriculture and open space and they have worked to make that happen,” he explained.

Chandler added that Fauquier is the granddaddy of them all, however, in terms of creating a comp plan and the accompanying tools to turn a vision into reality. Adopted in 1957, Fauquier’s comp plan focused “on directing growth to selected areas of the county and away from the other areas of the county. Land outside the identified areas was envisioned to remain rural in character use and function,” he said.

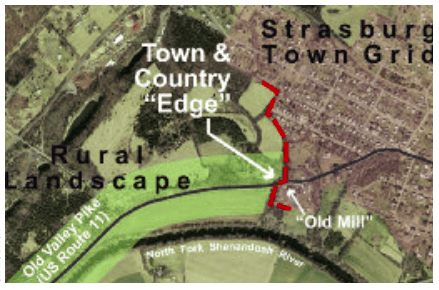

Design guidelines for Shenandoah County’s Old Valley Pike Corridor Plan reinforce a rural landscape design character in some stretches and a town design character in others, helping to maintain a distinction between town and countryside.

“It is important to note that the Fauquier comp plan prospered because, along with its supporting subdivision and zoning ordinances, the county implemented a rigorous infrastructure policy, which controlled where and when infrastructure (i.e., road improvements, central water and central sewer improvements)—if at all—would be built. Adherence to a policy of targeting and phasing new infrastructure in concert with the county comp plan is a primary reason Fauquier County has been successful in maintaining its rural character over the past 60 years despite its proximity to high growth localities,” he explained.

Chandler has one other recommendation. Localities should work together. “Developments have a regional impact,” Chandler noted. Counties and cities should start to fit their comp plan maps together with neighboring localities and begin to think regionally about shared boundaries and working together to accommodate growth, shared infrastructure, and common issues, he said.

In the planning world, it really does take a roomful of superheroes working together to win the day. The comp plan and accompanying ordinances absolutely have to be in order, but without the superhero sidekicks such as a build-out analysis, phased development, and a capital improvements plan, the dark side might still be victorious.

The good news is that there are plenty of good models out there to follow. “What you need is a strategy to achieve the future you envision,” Chandler concluded.

Comp plan guru Mike Chandler at a 2007 planning workshop held in Shenandoah County.

Nancy Sorrells wears many hats in the community. In addition to Augusta County Coordinator for the Alliance, she is a former Augusta County Supervisor, founding member of Fields of Gold agritourism initiative, freelance writer and Valley historian.