A few years ago, a group from the Shenandoah Valley gathered around a large conference table in the Washington, D.C. office of a top federal official. We were there to speak of the dangers fracking posed to our water. Several of us represented what are now Alliance legacy organizations.

George Washington National Forest Stream. (Courtesy of Striebig Photography & Design)

On the table was a tray with a large glass pitcher brimming with water. When my turn came to speak, I told the official that he needed to thank those of us from the Valley for that pitcher of water. My statement elicited a smile and an acknowledgment of the truth in my remark.

As you peruse this newsletter, you will encounter a lot of talk about water. “How is it,” you might ask “that the Alliance, an organization primarily focused on land use and conservation, devotes so much time and effort to water?”

In short, the answer is because the two—land and water—are inextricably linked. The Alliance mission envisions a Shenandoah Valley where our way of life is sustained by rural landscapes, clean streams and rivers, and thriving communities. The blue ribbon neatly tying those themes together is water.

Here in the Valley, three of Virginia’s most storied rivers—the James, the Shenandoah, and the Potomac—arise either partly or fully in the region served by the Alliance and flow through Richmond or Washington, D.C., sustaining life and quenching the thirst of 4.5 million people before draining into the Chesapeake Bay. More than 8,000 miles of headwater streams and springs begin on and flow through Valley farmland. Water fuels the economic engines of agriculture and manufacturing in the Valley, underpins recreational opportunities, and draws tourists from around the world.

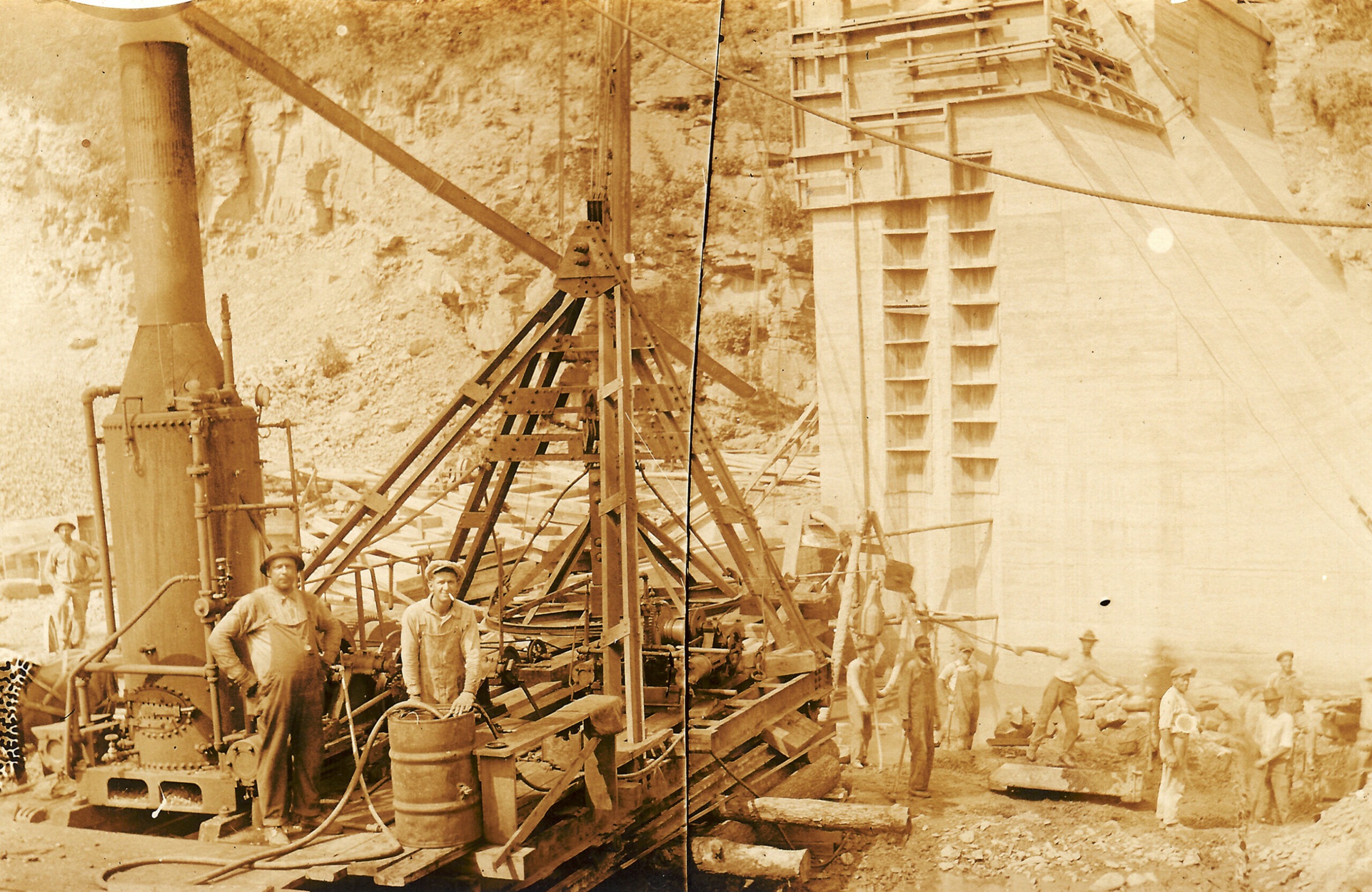

Built between 1924-26, the Staunton Dam is a cement structure 100 feet long and 40 feet high. (Courtesy Augusta County Historical Society)

In one way or another, water should be on the radar of every leader and planner in the region. In Staunton, for instance, residents turn on faucets possibly oblivious to the fact that clean water flows into their home from a reservoir more than 20 miles west in the National Forest. In the 1920s, city council had the foresight to capitalize on the promise of protection offered by the creation of the forest and solve water woes that had plagued the town since the 1700s.

With steam-powered equipment and mules, they went deep into the forest where the water was unpolluted and built a dam, tunneled 6,000 feet through a mountain, and laid miles of pipe bringing clean water to the city. A century later, the city sent divers to inspect and repair the dam and sophisticated cameras zipped through miles of century-old pipe in an effort to ensure clean water for future generations.

Public sewer replaced privies, like this one, located throughout Greenville. (Courtesy Augusta County Historical Society)

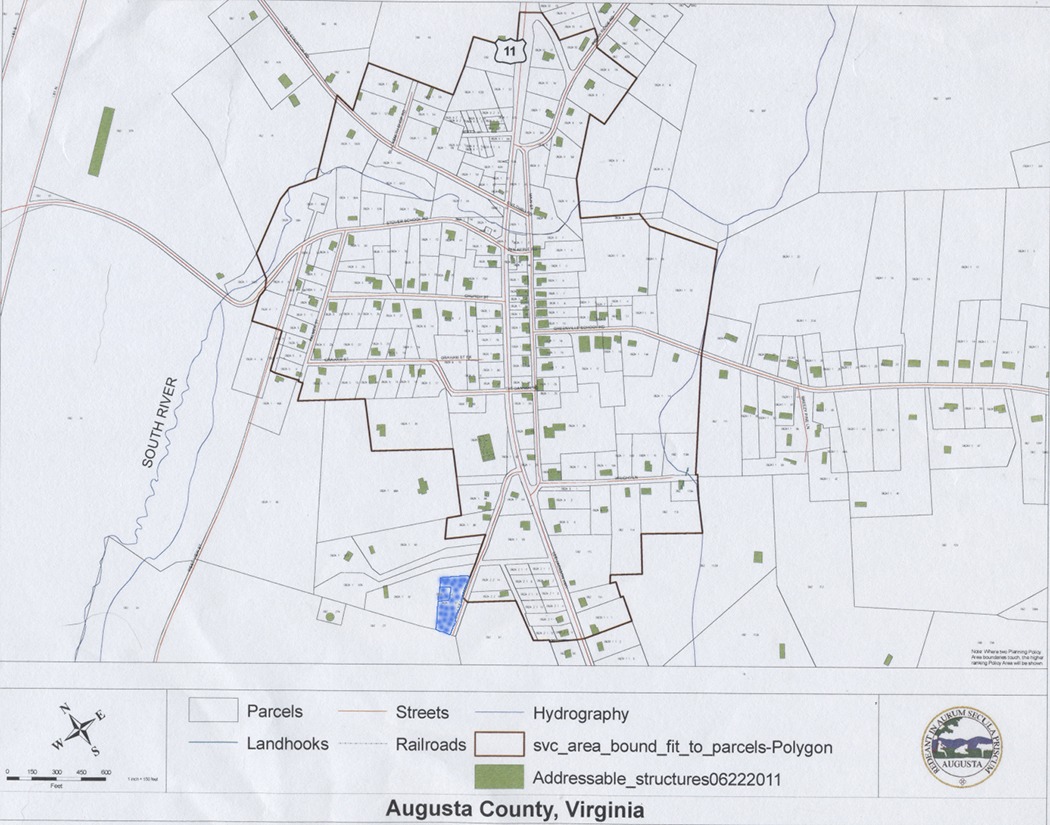

Map showing public sewer project area for the village of Greenville. (Courtesy Augusta County Historical Society)

In the southern Augusta County village of Greenville, citizens faced a tough issue a few years ago. The 18th-century village is bisected by the South River, a Shenandoah tributary that begins just a quarter mile away. Built a century before indoor plumbing, a third of the buildings had no known septic permit and several still relied on privies. The problem threatened not just the health and economic viability of the historic village, but everyone downstream, all the way to that water pitcher in Washington. Thankfully, a partnership used a clean water grant to bring public sewer to the village while protecting the surrounding area from potential unbridled growth and further water degradation.

For the Alliance, our work hosting the Shenandoah Valley Conservation Collaborative is critical to improving and protecting the Valley’s water quality. This regional partnership works to permanently protect farmland throughout the Valley, embedding and upgrading best management practices and watershed awareness in the process, resulting in healthier soil, cleaner water and a more resilient Chesapeake Bay.

The Alliance is also assisting with a new project that is identifying local public water utilities that could benefit from expertise on how to refine drinking and wastewater systems to improve water quality and reduce taxpayer bills.

North River in Rockingham County. (Courtesy Project367)

And, on the ground, each county coordinator keeps water quality at the forefront every day in local planning from a locality’s comprehensive plan and zoning language to specific development proposals like utility-scale solar, transportation, and pipelines, as you’ll read about in later sections.

In reality, there is no project involving the Valley landscape and its communities that doesn’t have a splash of water concern. By always valuing clean water as a precious resource that infiltrates the Valley’s quality of life and eagerly promoting projects with clean water components like the ones discussed here, the Alliance helps to ensure that the future generations who reach for that glass of water will do so without fear.

Nancy Sorrells wears many hats in the community. In addition to Augusta County Coordinator for the Alliance, she is a former Augusta County Supervisor, founding member of the Fields of Gold agritourism initiative, freelance writer and Valley historian.

Top photo is Meadowview Farm in Augusta County, courtesy Bobby Whitescarver.