Retired soil scientist, farmer, and author Bobby Whitescarver sums up his take on the value of streamside buffers quite simply: “Fish live on trees.” When those words flow out of his mouth, one can’t help but envision a world where fish perch precariously on branches and, together with the birds, flit in and out of the foliage. But Whitescarver is not talking about a fantasy world; instead he is simply reducing the concept of streamside buffers and their value in producing clean water, keeping people and livestock healthy, fueling productive family farms, and supporting wildlife, into one neat, catchy little phrase.

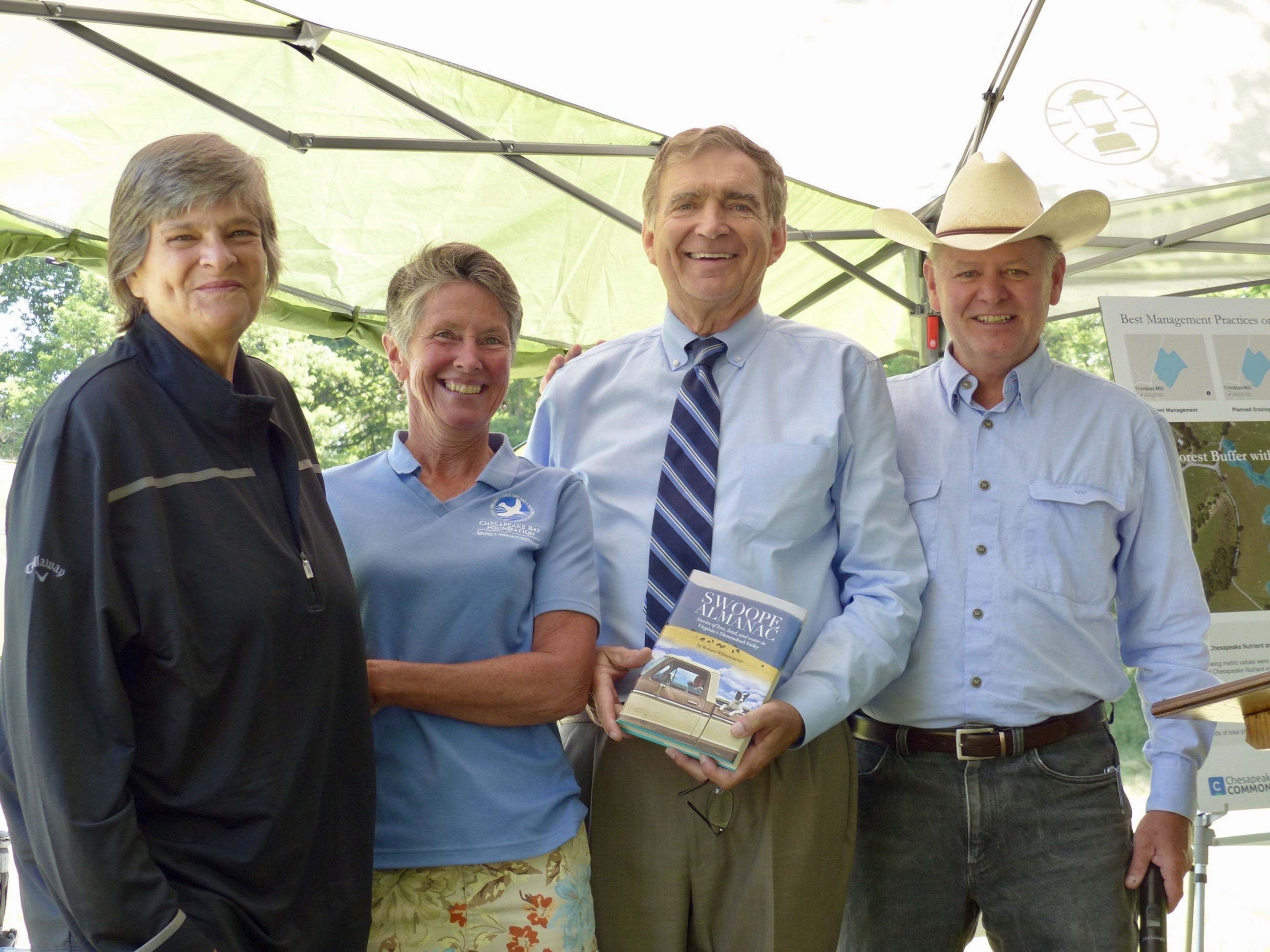

Farming has been the number one business in the Shenandoah Valley since the first settlers arrived in the early 1700s. But the idea of being better farmers by helping the environment is a relatively new concept. Bobby and his wife Jeanne Hoffman, a life-long farmer and a descendant of those first Valley settlers, are living proof that agriculture and conservation can work together with the end result being a more productive farm and clean drinking water. Their tool for making this work is a streamside buffer.

Fencing livestock out of streams is beneficial for farmers and for everyone downstream, but it can be eight times more beneficial if trees are planted along the stream as well.

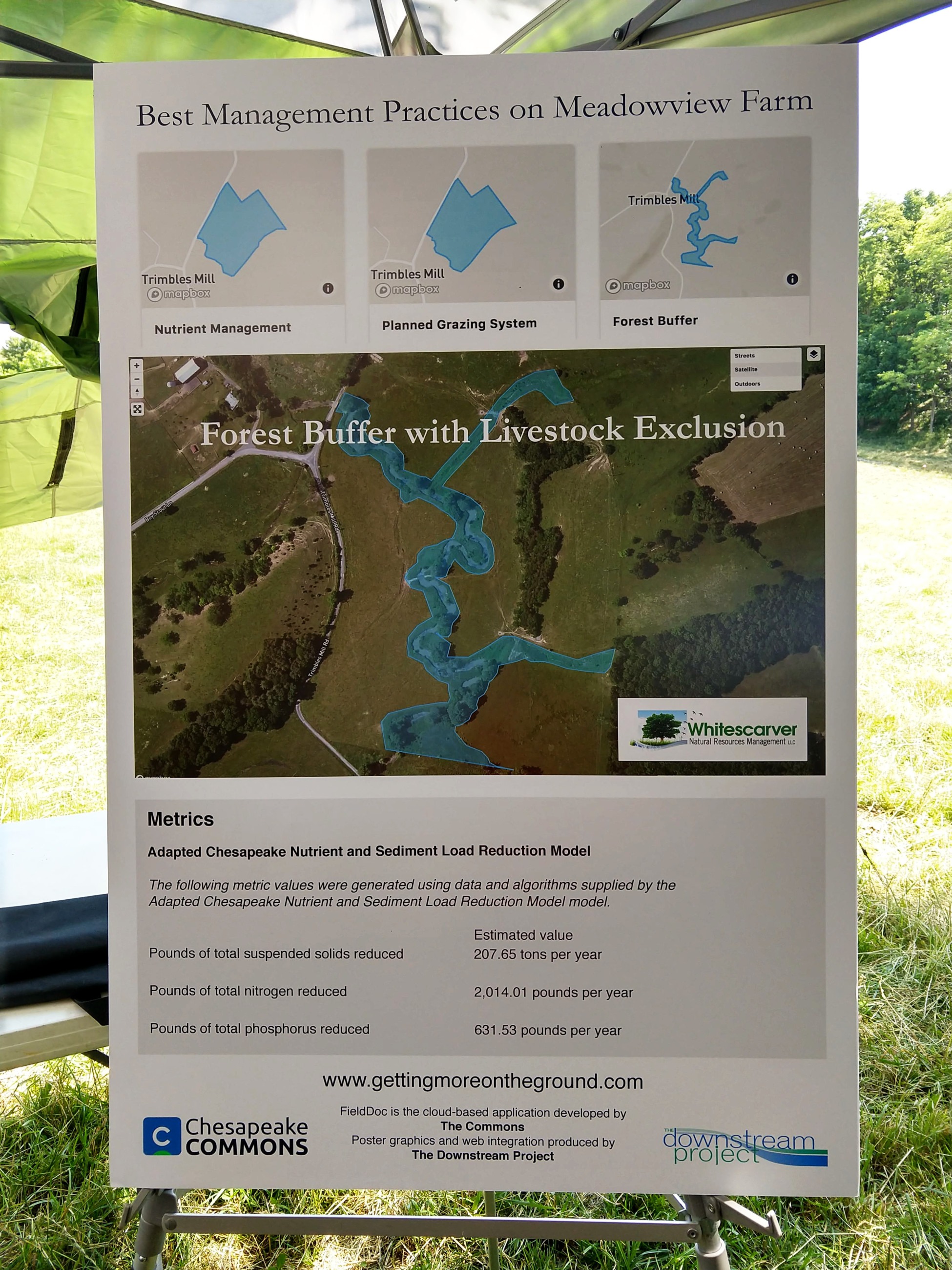

This nexus of agriculture and conservation is exemplified by the half-mile streamside buffer that Bobby and Jeanne have planted along a stretch of the Middle River (a tributary of the South Fork of the Shenandoah) in Augusta County. Fifteen years ago the water flowing through their farm often looked like chocolate milk because of the cattle on their farm and those upstream who were in the river. Not only do cattle poop in the river, but their hooves rip up the stream banks and send dirt downstream. The result was unhealthy livestock and people because of the high levels of E. coli in the water (bacteria from animal waste) and an unhealthy river.

Their problem was no different from that faced by farmers throughout the Valley, where the state’s most productive agriculture thrives. The solution to the problem? Fencing the livestock out of the waterway and planting trees. The result is a win-win for the farmers and the local community.

Just getting the livestock out of the stream is huge according to Bobby, who noted that when E. coli levels get too high both livestock and people often suffer gastrointestinal ailments. Further, pregnant cattle sometimes give birth near streams creating a “calving risk area,” he said. “The mother cows go to the water, have a calf, and it drowns, and that happens a lot.” So fencing off the streams immediately helps a farmer’s bottom line in the account books.

But part two of the streamside buffer story – planting trees – helps everybody’s bottom line. The trees shade the water and lower the temperature, thus creating a better habitat for the aquatic life, tree roots hold the soil in place and keep it from washing downstream, and the leaves from the trees drop into the river where they soon become another critter’s lunch.

“Fencing livestock out of streams is beneficial for farmers and for everyone downstream, but it can be eight times more beneficial if trees are planted along the stream as well,” Bobby explained.

And that gets us back to the fish living on trees…sort of. Here’s how that works. A healthy stream is filled with aquatic macroinvertebrates – the larval stage of insects that are the vacuum cleaners of the streams. These spineless critters, large enough to see with the naked eye, spend most of their lives shredding and eating leaves that fall into the stream. Eventually they turn into winged insects such as mayflies, caddisflies, and stoneflies. Fish love to dine on the larval stage of those water critters that are spending their lives shredding leaves and cleaning the water. It’s the circle of life, but it all starts with keeping the cattle away from the stream and replacing them with trees.

“Leaves from streamside forests are the main food source for macroinvertebrates. It’s the bottom of the food chain for trout and other fish. No leaves, no insects, no fish. Not only do trees supply food for the insects, they also provide shade, which keeps the water temperature cool and prevents intense direct sunlight, as opposed to dappled sunlight, from reaching the stream,” Bobby added.

Or, to put it another way: “Fish live on trees.”

Fifteen years ago Bobby and Jeanne created a streamside buffer on their farm on the Middle River. They did their part by excluding the livestock and planting some trees. Mother Nature and her wildlife helpers then added their touch by planting even more native trees including walnuts, sycamore, and willows and native plants as understory.

Between their planned work and Mother Nature’s finishing touches, there is now a diverse, lush green corridor along the Middle River as it meanders through their farm. The river is out of sight even to those standing just a few feet away, but one can hear it babbling along its path north through the Shenandoah Valley. The tinkling sounds of the water mix with a cacophony of birds and insects that reflect the obvious fact that streamside buffers with their trees and understory of dense native vegetation provide many bonuses including wildlife corridors and habitat.

When you add it all up – the people, the water, the livestock, the wildlife, and the economy – it is easy to see why Bobby says “streamside forest buffers are the single, most cost effective best management practice for non-point source water pollution in the rural landscape.” Or, in other words, “fish live on trees.”

Thanks to these contributors

The Alliance is proud to have Bobby Whitescarver as a founding member of our Board of Directors, and we are thankful for his leadership as we work to get more streamside plantings in the ground with new funding from National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. If you would like to learn more about streamside buffers or follow Bobby and Jeanne’s adventures on their farm in Swoope, Va., go to www.gettingmoreontheground.com/swoope-almanac/ to order a copy of his new book Swoope Almanac: Stories of love, land, and water in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

Guest Feature author Nancy Sorrells wears many hats in the community. In addition to Augusta County Coordinator for the Alliance, she is a former Augusta County Supervisor, founding member of Fields of Gold agritourism initiative, freelance writer and Valley historian.