Joan and Walter Brown have given a lifetime of service to their community and built a legacy for descendants. The Browns long ago retired from public service careers as a police officer and a public school teacher, but they continue to volunteer and operate a small family farm in Augusta County.

You would think that after 54 years of marriage, it might be time to slow down, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. As African Americans, the pair gained strength from living principled lives in a sometimes-unprincipled world, often swimming upstream against educational and societal challenges.

Walter, 82, was one of eight siblings born on the family farm where they still live. “I thought growing up on a farm was great,” he remembers. “We milked every morning, fed the hogs and did whatever was necessary. We would take our grain to the mill by horse and wagon.”

Hidden Springs Farm, operated by Walter and Joan Brown, is not only a Virginia Century Farm, but is one of the last African American farms in Augusta County. Here the Browns stand next to one of the essential pieces of machinery on the farm—the tractor. (Photo by Nancy Sorrells)

Life on his parents’ farm (Noah and Mary Ella Brown) gave him a sense of privilege he recalled. “I can’t ever remember missing a meal. Did we have money? No. But we had the necessities of life.”

Owning land and getting an education were paramount in his family. Although his father only completed third grade, he worked to secure the best possible education for his children. If that meant hitching up his horses to help in constructing a new school or driving a school bus that he fashioned out of a Model T truck, that’s what happened.

Nobody went hungry on a farm in Augusta County according to Walter Brown. His sister, Ester Brown Williams, is seen working the garden on the family farm. (Courtesy of Walter Brown)

Noah Brown, Walter Brown’s father, believed owning land and getting an education were two of the most essential pieces of life. (Courtesy of Walter Brown)

Hog butchering time was an important activity on any farm in the Shenandoah Valley. Seen here is Walter’s brother, Noah Brown Jr., helping with butchering at Hidden Springs Farm. (Courtesy of Walter Brown)

Joan, 81, who grew up in the West Virginia panhandle where her mother cleaned and her father labored at a paper mill, wanted to be a pediatric nurse but eventually switched to education. Academic awards got her to college and a diploma at Shepherd College where she was the only African American in her graduating class. Her degree in education gave her certification in health and physical education and driver’s education with a minor in biology.

Her first job was at the same Augusta Training School that Noah Brown helped build and where Walter graduated. She arrived in 1963, three years before the county’s public schools desegregated.

I told the kids, I don’t know what color I am until I look down. I am a teacher first and I don’t care what color you are either—Black, blue, or green.

Walter’s career path was more circuitous than that of his wife. After finishing high school, he spent three years at Norfolk State majoring in industrial education before money got tight and he enlisted in the army. After three years, he returned home and soon found himself taking the Staunton police entrance exam.

Joan and Walter met at Smokey Row Baptist Church and were married in 1966 on the Brown family farm. That was the year county schools desegregated. Joan moved to Wilson Memorial High School where, as the girls’ softball coach, she quietly made history as the first Black coach in the integrated schools. By the time she retired, she had taught and coached 32 years. “I told the kids, I don’t know what color I am until I look down. I am a teacher first and I don’t care what color you are either—Black, blue, or green,” she said.

When they saw Lt. Brown coming, they weren’t expecting ‘this.’

After acing the police entrance exam, Walter became just the second Black person on the Staunton force. Walter rose in rank, becoming the city’s first Black officer, and helping to found a regional a regional police training academy that gained national recognition. As a result, he traveled around the country helping other law enforcement agencies.

That was back in the seventies when the idea of a Black police officer in charge of training was a new concept. “When they saw Lt. Brown coming, they weren’t expecting ‘this’,” Walter said, pointing to his brown skin.

There is pride in having your own farm. I am going to hold onto this for my daughters and my nieces and nephews. I know that it makes them feel good to have that legacy.

Although his profession was law enforcement, Walter’s passion was farming. He has continued his father’s farm, raising beef cattle and caring for the land. Hidden Springs Farm, named for its powerful 300,000-gallons-per-day spring, was the first in the county to incorporate a USDA easement to protect that water.

These days, farm operations have slowed to a few cattle and an occasional crop, but Walter is proud of being one of the last African American farmers in Augusta, a family tradition that stretches back to just after the Civil War when his grandfather Charles Brown bought a farm in southern Augusta, then added the current farm in 1896. That land passed to Noah and then Walter.

Walter Brown’s grandfather, Charles Brown (seated), is surrounded by his family in this photo. Charles Brown, born a slave, was the first member of the family to own land and instilled in his children and grandchildren the value of owning land. (Courtesy of Walter Brown)

Years ago, Walter registered Hidden Springs as a Virginia Century Farm, a designation given farms operated by the same family for over 100 years. The official designation means a lot to the Browns.

“At one time, in the Arbor Hill area, there were about 2,500 acres of African American owned farmland. Today there are about 100 acres. The wealth of the Black community has been lost,” he said.

Walter and his brother calculated that a century ago there were 10,000-12,000 acres of Black owned farmland in the county. Today Hidden Springs is among the last.

“One time, Dad and a white neighbor were working together on a fence and the neighbor said ‘someday all of this land will be mine.’ My dad silently vowed that was never going to happen and he instilled in his kids to hang onto their land,” Walter said.

“There is pride in having your own farm. I am going to hold onto this for my daughters and my nieces and nephews. I know that it makes them feel good to have that legacy,” he said.

Walter paused and made a final, thoughtful observation: “Owning a farm is the reason why my grandfather, an illiterate Black man born a slave, could vote. It was because he had land. That is the truth of it.”

Feature author Nancy Sorrells wears many hats in the community. In addition to Augusta County Coordinator for the Alliance, she is a former Augusta County Supervisor, founding member of Fields of Gold agritourism initiative, freelance writer and Valley historian.

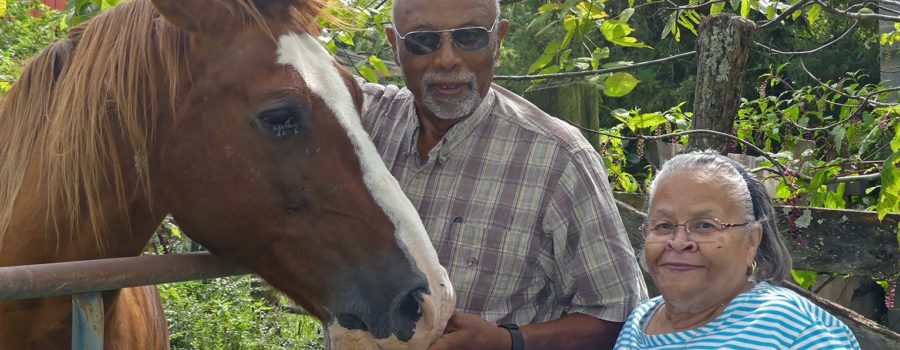

Banner Photo: Walter and Joan Brown of Arbor Hill in Augusta County stand next to Billy the farm horse. (Photo by Nancy Sorrells)